Before I post the excerpt, some thoughts~ Tonight’s Full Harvest moon coincides with our busiest time on the croft, namely, The Harvest. Writing must be curtailed to a couple hours in the mornings, to leave enough time for ripening veggies, apples, and the daily watering chore. We’ve had a much too-dry year here in northeast Wyoming. Fire danger is high. But this evening, oh joy! two welcome events–three, if one counts a Full Moon–our son comes for an overnight, and rain is expected.

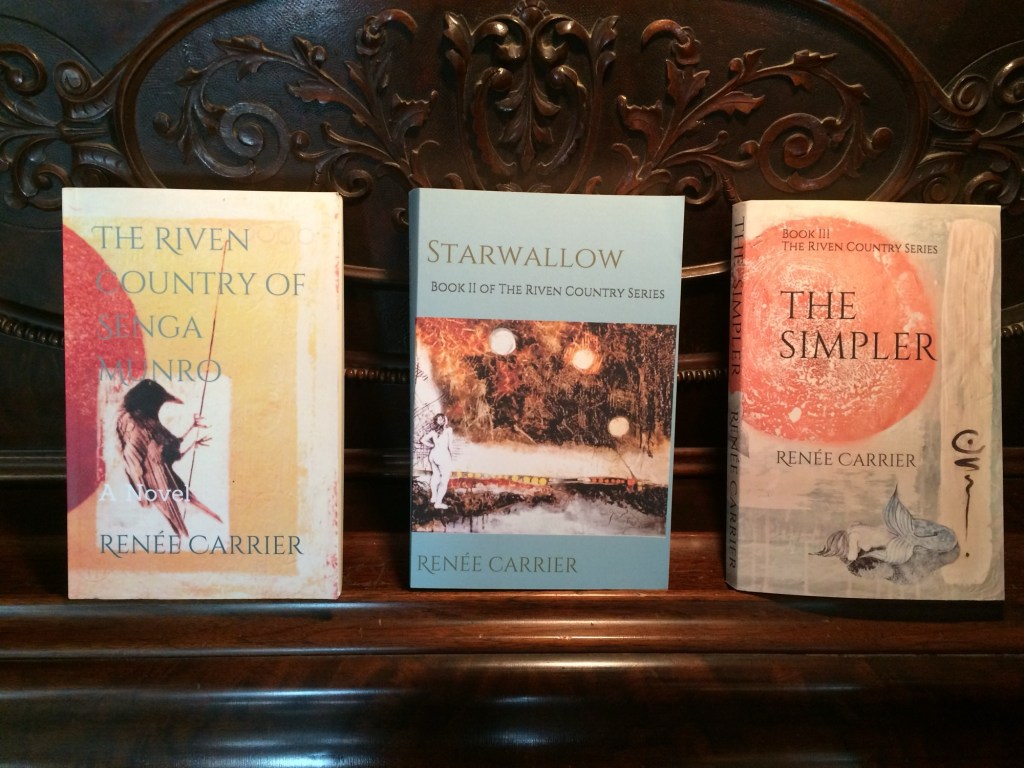

Regarding my progress on Book IV of the Riven series (and the final installment) I am nearing the end of the first draft. Lately, I’ve heard several adjectives describing what I <think> it is, genre-wise. “Speculative fiction,” Visionary fiction,” and “High Concept novel” top the list. Yes, to each. So there’s that.

So, an update to readers, and if you don’t mind perusing a rough draft passage, here’s one taken from the beginning of the fourth book, working title, The Earth is Her Own:

She who invited mystery had joined the ranks. Senga Munro was gone. Even her cabin was gone, burned to the ground by a dry-lightning strike. The shrine to her daughter, a juniper tree, gone. Strange the orchard had survived, the garage too. Gabe had contacted Senga’s cousin, having discovered his phone number jotted in the herbal notebook. Colin had said little—except to note a sizeable check had been cashed per her stipulation, should she die.

Appropriating the literary, Gabe referred to “the `sick villain, Tom Robinson,” not in his right mind, as they say, who remained committed to the state hospital in Evanston. Rob McGhee had yet to arrive to collect the unearthed Walker’s Shortbread tin containing his and Senga’s daughter’s ashes—apart from the surrounding gray powder.

Emily-Who-Loved. Gabe pictured the epitaph, once painted on the back of the child-size chair. It had guarded the cookie tin’s resting place. The girl had fallen from a cliff twenty years before. Gabe wanted to think she and Senga were reunited, but who knew?

His sweet Francesca had left the week before—her yearly homeland visit—the tables turned. “Now I live in America and visit Italy,” she’d declared at the airport. Their wedding date still on hold, for one reason or another—mostly logistics. Her mother, impatient, labeled it an excuse; Does he really want to marry you? But Gabe knew the woman’s predilections and didn’t give the complaint a second thought.

He had awakened early and would have rolled over for another hour of sleep, having the bed to himself, but no; best rise. The camper was cramped. He and Francesca had worked out the dance (as they called it) to negotiate movement, her Rubenesque figure a factor. A do-si-do! he had joked, having to demonstrate. She’d smiled. Do-si-do. Another term for her growing list of English idioms.

After stretching, he yawned and propped on an elbow to look out the window. A clear sky. In the cold November dawn only Venus shone, then his sight fell to the bright stained-glass shade in the window of his former quarters across the way. “Damn,” he muttered aloud, “. . . where is your head?” The tack room in the barn continued to serve as his study. He cursed again under his breath, having apparently forgotten to switch off the light the night before. After the last chore, his new story had seized his attention and he had worked until two in the morning.

Another story nudged him now.

Gabe Belizaire claimed fifth generation honor by his family (as far as he knew) to have lived on a ranch in southwest Louisiana. His great-great-grandfather had been assigned the surname by his owners—a belated comprehension never failing to cause Gabe considerable cognitive indigestion. What began as an equine breeding farm had, over decades, evolved into a rodeo stock ranch. Savvy hires and a good deal of loyalty had kept the operation viable, despite hurricanes, drought, and The Great Depression. The land itself required constant renewal, and heroic effort had been expended in improving the fields, pastures, and ponds.

The way of life had appealed to Gabe’s ancestor, Thomas, who chose to remain after Emancipation. The original Famille Belizaire was long gone; the farm (or “ranch”) was bought out and managed over the years by various proprietors. Gabe’s family, past and present, supplied the thick, dominant cord of continuity; but it appeared it might end with him, as he had decamped to Wyoming.

I don’t even know where that’s at! his mother had once exclaimed.

Squeezed between Montana and Colorado, Wyoming boasts or bemoans the lowest population in the country. The Black Hills occupy less than five percent of the big state’s roughly 98,000-square-mile land mass. Where someone hails from necessarily factors into where one winds up (Where’ you from?) and unless one hefty eagle stole away a sleeping newborn and flew hundreds of miles to deposit him in a high eyrie, to be discovered by a plucky feather hunter and fortuitously saved by adoption into the tribe. . . .

Well, we’re all settlers, even now, Gabe had once ruminated after overhearing his boss’s wife, Caroline, refer to their hired man as “just another white settler.” Despite his coal-black skin. She had a way with words that he liked. No filter, for the most part, but a good woman. Best-hearted.

These musings were nudged aside by the horsey photograph his sweet Francesca had stuck to the bathroom mirror.

Gabe had once put in long hours on The Black. The horse belonged to the thorn in his flesh—the owners’ daughter, Camilla Williams. Another high-spirited filly. He excused the gratuitous comparison, if only for the truth. That the animal was called The Black held more significance to the girl than to Gabe or his family—though he could seldom fathom his sister Allie’s thinking. It was Allie who’d snapped the picture that day, after telling her father and brother to say cheese. At fourteen and fifteen, Allie and Camilla were close in age, but centuries apart in sensibilities.

After the pause for the photograph, and a quick cup of water from the pump, horse and rider logged another hour practicing fundamentals in the arena (walk, trot, lope, half-halts, turns) until both dripped with sweat—temperature and humidity reaching the same high. Gabe reined the filly to the gate, swung his leg over her long neck and jumped down, The Black’s head jerking up with the unexpected movement.

“You scared her, dumb-ass,” came a voice. It belonged to Camilla.

“Hey. Yeah, but now she knows.”

The girl emerged from the shadow and shade of a spreading oak tree, one of the few old timers left. Gabe wished he had worn a tee-shirt.

“When can I ride her?” she asked, peering at his glistening shoulders.

“Oh, let’s give her another month, at least. Daddy thinks that’s all it’ll take. She’s smart, your horse.” This to confirm what was what and who was who.

“Hunh. Well, I think she’ll be ready before. See ya later, Gabe,” said the girl. Then she made a sound similar to the one he often heard her mother make when trying to make a point—not quite another hunh (as he would later write it), but dusted with a sprinkling of self-satisfaction. Camilla turned toward the once stately old home; sadly, both in dire need of restoration.

He watched her stroll away as he wiped his forehead with the back of his hand, then he took a breath and slowly exhaled. The smell of horse sweat gave him comfort.

Copyright 2024 Renee Carrier